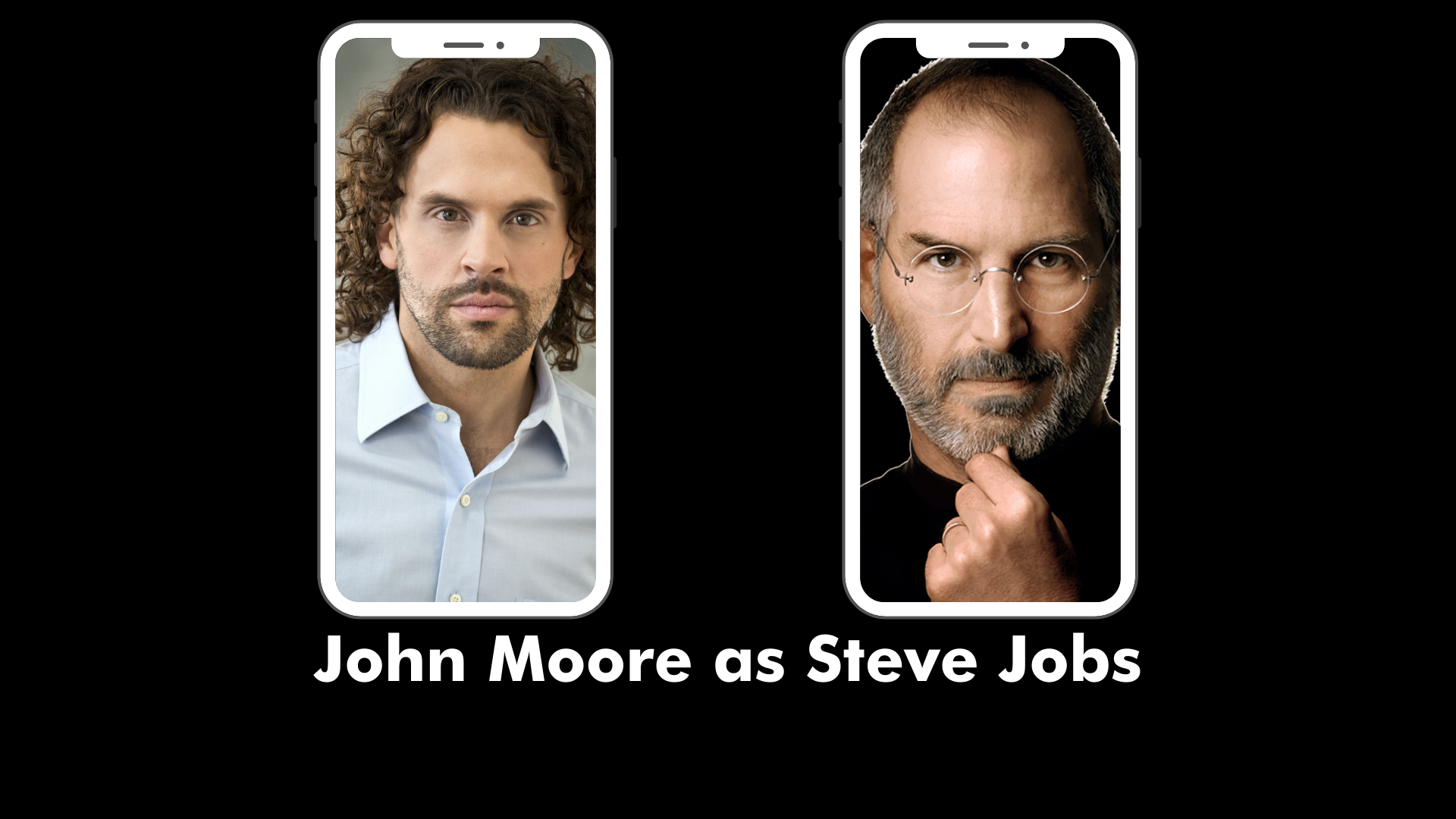

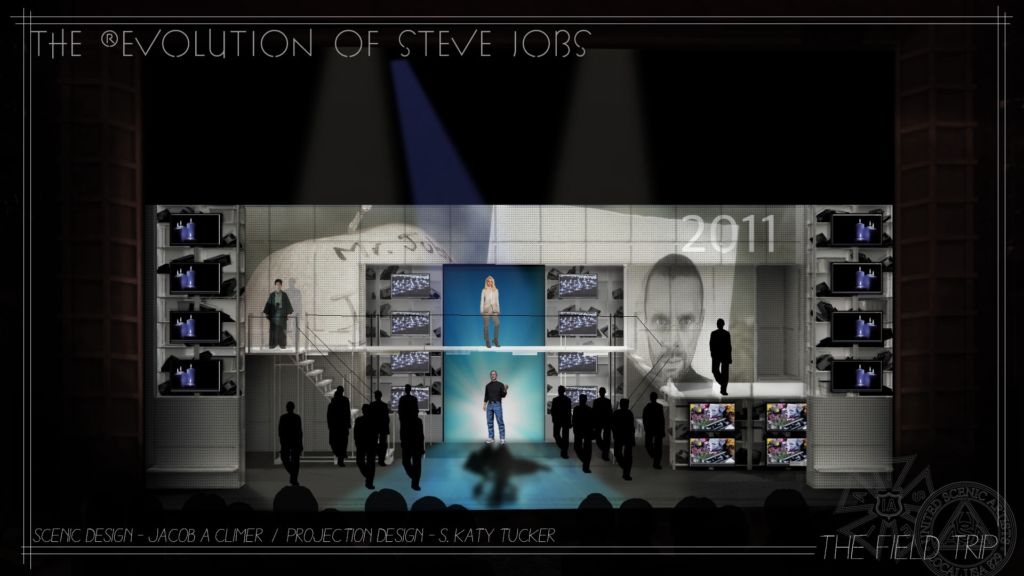

This article appears in the performance program for The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, taking place at the Long Center on February 3, 5, & 6 2022. Find out more about the show here.

John Moore: When I was first preparing to sing the role of Steve Jobs, I knew I needed to read his autobiography, written by Walter Isaacson. But instead of reading a hard copy, I decided I should listen to it instead. So, playing it on my iPhone, listening with my Air Pods, and tracking my walk with my Apple Watch, I walked and I listened, and it felt like the sort of walking meditation that Jobs himself would have done.

I believe that this opera is one of the first successes in tapping into what it means to build a legacy around the character of Steve Jobs. There’s been the autobiography, and of course, we’re all basically carrying around his legacy with us every single day in multiple ways. His vision has infected so many of the products that we all have or desire to have, and not just those made by Apple. I appreciate the fact that there were thousands of engineers and salespeople working to bring us all these devices, but Jobs has become the modern icon he is because he was a true cultural leader. A genius. To me, that’s the beauty of leadership, that one person can infect a global culture with only their presence and their ideas. What pours forth from them is the thing that brings out the best attributes in the people working in that landscape.

The seventy minutes of storytelling that we get in this opera, through Mason [Bates]’s music and Mark [Campbell]’s words, humanize Steve Jobs even though he is that contemporary icon. We’ve all heard that he could be extremely difficult, and all of the elements are there to make it easy for us to brand him as an a*****e. But that’s what I love about theater. If we’re listening and we’re paying attention to this piece, we will find the human being within that a*****e, and I take my job of portraying him—of revealing his humanity to the audience—very seriously.

I recently came across a documentary about him on YouTube, and one interview in it really connected me to the human aspect of him. It was with an engineer who worked for Apple in the 1980s, and in the first part of the interview, he talked about what it was like to work for such a taskmaster, someone who had no problem berating, destroying, and firing you if you didn’t say the right thing in the right moment. Yet, almost at the end, the documentary makers showed him again and he was in tears, talking about Steve Jobs bringing out the best of him, which was something that allowed not only for his own life to be made better, but also the lives of his closest loved ones. And that really struck me. Can a man who is such an “evil boss” in the office, really go and do silent meditation retreats when no one’s watching?

There’s something so profound about that, and we tap into it in the opera. Mason and Mark give us moments when, alongside the drama that’s happening on stage, we can actually reflect on our own lives, and our own use of technology to connect with each other and also with ourselves. How many more people have downloaded mindfulness apps on their iPhone since this opera was first written? How many people are going to hear the tones in the orchestra, the drones and the electronic music, the bells and the gongs and are going to be transported into their mindfulness practice? And who was it that gave us those tools for internal reflection? Well, the guy we’re watching on stage. It’s one of the things he talks about. He knew how to get the best out of people and he knew that everybody is capable of greatness.

The other important character in the opera is Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve’s widow. She’s the only one who can call him to task, she calls him silly, and she’s able to laugh at him. Anyone who’s been in a relationship will understand what it’s like to have someone who can laugh at you, yet you don’t tear them apart, disown them and ostracize them. You love them because they are in you know. Those relationships are fundamental and foundational to what it means to be alive.

Mason has written a very accessible tonal melodic score, and what adds great value to it are the soundscapes he has created. When I was learning this role, I listened to the recording of the original production so that I could mentally set my own part within the technological sound-world Mason has created alongside the music. He’s used electronic sound and amplification of the singers to add to the art, not to remove from it. I know that amplification can be a controversial move in opera circles—the purists hate it—and I’ll admit, it was a mental challenge for me too at first. But I’ve grown to realize that holding on to such an elitist mentality can be limiting.

When I began my professional career, I thought that one of the coolest things about being an opera singer was that I had such a highly trained voice, I was powerful enough to sing over a seventy-piece orchestra in a four-thousand-seat hall and be heard in every seat. But as a person that worships the jazz idiom, I came to realize that part of that love comes from listening to those virtuosos on their instruments painting sound with a full palette of colors, and that most of the time, even though they’re in small spaces—even the Village Vanguard in New York City only holds about eighty—they use microphones. They don’t need the added effect of sheer volume to be impressive. In fact, they often use the amplification to add to their performance. At the end of a really beautiful saxophone solo, the instrumentalist can finish with a vibrato created merely by moving air through the horn, but because it’s amplified, you get the final coda on the back end of what was just this marvelous, virtuoso performance.

In the same way, think of the difference in listening to an opera singer in a chamber music setting, rather than a full operatic performance. Because the singer isn’t focusing merely on carrying well over the orchestra in all registers and in all dynamics, they can really concentrate on telling the story within that intimate setting. I recently did a concert back in the beautiful church in the small town in Iowa I grew up in, and part of this concert was an acoustic Samuel Barber song. I was able to let my full body sing it, and it felt great. But I also did this wonderful Alec Wilder song that I used a microphone for, and for those ten minutes I got to play with the totality of that space and explore that song’s story with my voice.

That’s the gift that amplification gives us in Steve Jobs. One of the magic tricks of this piece is that there’s still the big orchestra, but there’s also a click track going. It feels like you’re at a club and Mason Bates is the DJ. He adds so much to the music with all the other sounds, yet you don’t lose any of the nuance of the totality of the human voice. All of the singers are still those highly trained opera singers that can sing over an orchestra with no microphone, but in this piece the magic of the amplification is as potent a technology as, say, electronic lighting was when it was introduced into the theater instead of candles in the footlights. Suddenly, there was a brand new art form of stage lighting. It enhanced the show, and certainly didn’t detract from it.

Obviously, I’m not suggesting that we amplify all the traditional works which were written for performance without it. What I’m saying is that we should accept and enjoy this beautiful addition to our opera repertory. We should be excited that we get to experience this new form of opera while it’s still in its nascent phase. I don’t judge anybody for lauding and cherishing past conceptions of what it means to have “the operatic experience”, but we also need to look at how all art forms have developed over the last seventy-five years by learning from each other. When moving pictures, and then television, began they borrowed heavily from theater, dance, and opera. And now, theater, dance, and opera are borrowing things back from film and TV. They’re tapping into projection and amplification, and even into CGI special effects, and giving audiences an experience that the traditional theatrical arts cannot. It’s such a beautiful opportunity and I really think we’re going to see more and more of it.

Ultimately, any person who loves to go to a hall and hear beautiful music-making—even if they think that opera is the last place that they should allow advanced technologies—is going to be amazed by what they’ll experience in The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs. It’s people like Mason Bates, Mark Campbell, and Tomer Zvulun that are allowing this developmental shift in opera to happen, along with everyone working at companies like Austin, Kansas City, Atlanta, and others. They’re at the forefront of that “new opera revolution” and it’s a beautiful thing to be a part of it. I love using my whole voice, not just the volume it can produce, and it’s this factor that allows for this story to take front and center in my performance.

The other thing I’m sure about is that new operas not only extend the art form, but they also extend the audience, perhaps through subject matter like the life of a tech icon like Steve Jobs, but also because, generally, most new operas are short and therefore are more accessible to newcomers. Certainly, the few new pieces that I’ve done are mostly only around seventy minutes long, so it’s almost like they act as a taster for the full operatic experience. In most traditional operas, seventy minutes only takes you to the first bathroom break, which can be intimidating for first-timers. So if someone decides to go to see this opera on a whim, simply because it’s about Steve Jobs, then those seventy minutes could well plant a seed that they’re willing to let grow. Soon, they’re willing to pay a little more attention and spend a little more time on this thing called opera. So we offer the short form, that actually gets them interested in the long-form. Sure, thanks to our technology, we now all have much lower attention spans, where we’ll only read the first half of an article, or listen to the first half of a CD, etc, but the thing we haven’t calculated yet is how technology then helps us when we’re desperate to go back and pay more attention. They want to have a medium where they can go spend more time, where they are not always rushing, where they can think deeply about what it means to be human. And of course, that’s what the theater is.

It’s pretty profound that we wake up in the morning and check our phones before we kiss our spouse. And that we tell our phone more intimate details than we tell our wives, husbands, children, or parents. Our phones know more about us now than we know about ourselves. Yet we still need a space in which we can come together to reconcile this tremendous change in our human physiology and our consciousness. Steve Jobs undoubtedly gave us a tool which allows us a greater understanding of ourselves, but what is reassuring to know is that while new technology might add to our artistic experience, it can never replace it.